Read Part I of Eli’s story here and Part II here.

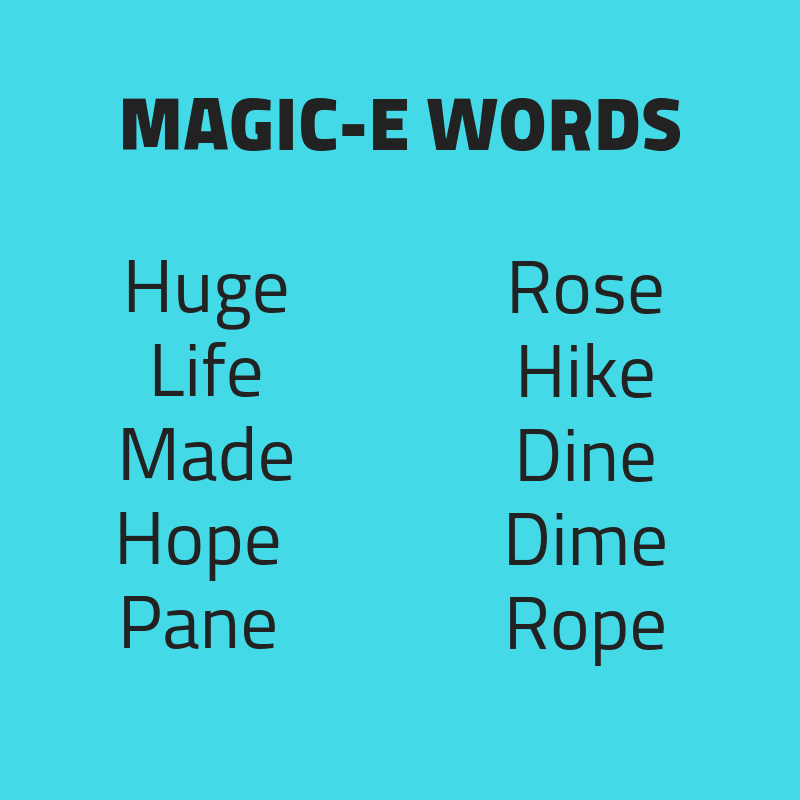

The classroom teacher provided young Eli with a list of spelling words. Eli, now in the third grade, worked with “Magic E” words—vowel-consonant-magic-e words. The spelling word list was not inspiring. Yet, I work with them anyway, knowing my goal is to make sure students are successful in the classroom.

The teacher believed she was giving the vowel pattern consonant-vowel-consonant-magic-e without acknowledging the difficulties young Eli was having with both words and an easily identifiable pattern.

When the vowel changes in each word, it is not a pattern. It’s a new word, with no pattern. A word pattern would look like rope, hope, slope, cope; there’s only one change with the consonant at the beginning, followed by the same vowel pattern. It also allows the teacher to assist with the consonant blends, which are very difficult for struggling students to hear. Mixing huge, life, and made all in the same word list, the teacher is asking the student to access too many different sounds, more likely leading to confusion.

As we begin our lesson reading the list of words, I find my tray of plastic alphabet letters. In this early stage of learning, using manipulatives (physical tools for teaching) allows a student to simply pick up a letter and not have to write it. It makes learning multi-sensory.

Eli finds the appropriate letters and chooses to stand between two chairs. He places letters on either side of him to create a word. He’s moving, listening, and is engaged.

We work on the word huge.

I read the word out loud, stretching out the sounds of the word “h-u-g.” My arms cross my chest as I say the letter “e.”

“The ‘e’ is silent,” I reinforce with this movement.

“Find the letters h-u-g,” I repeat. Eli responds appropriately. “Now the last letter,” I continue.

All appears to go well. Eli follows my instructions, finds the letters for the words, and puts the letters down in the correct order, creating the word huge. I believe we’ve finished our lesson and Eli gets it.

For the last couple of sessions, we work with a book on the planets in the solar system. Marshmallows are used to represent planets—the bigger the planet, the more marshmallows! Eli enjoys this learning activity as we place marshmallows on the poster and write a sentence under each planet.

Now, I refer to the sun in our solar system.

“The sun is the center of the solar system,” I tell Eli. “It is huge.”

We grab a pile of marshmallows and place them in our circle for the sun.

“Can you write the sentence, The sun is huge?” I ask him.

Eli writes: The sun is cuj.

I am stunned.

He hasn’t got it! I think. He’s not getting these spelling words at all! I thought working with the letters and sounds had been enough. But he didn’t have a clue; he couldn’t make the connections.

I know it’s in the teaching.

“Eli,” I say, opening the browser on my computer, “let’s get a picture for each of your spelling words.”

I type in sun into the images search engine and find a host of fantastic pictures.

“Which one do you like, Eli?”

He chooses one picture, and I cut and paste it to a word document to print.

“What size is the sun, Eli?” I ask.

“The sun is HUGE,” he replies with his arms stretched wide, with a huge smile to match.

Together we find pictures for the rest of his spelling words and print them.

Placing our selected pictures in front of Eli, I ask, “What word goes with this picture?”

Eli chooses the right word.

“Can you spell that word?” I ask with delight, yet concern.

Eli now responds with the correct word, spelling huge and every other word appropriately!

Over the following tutoring sessions, I learn that if I ask Eli to just spell his words—like one does with most students—he gets them wrong. He appears to have no idea of the word, the letters, or the sounds. However, when I suggest: “Let’s look at the pictures of your spelling words. Now look at the image and ask, ‘Which word goes with this picture?’” Eli says both the sentence we had written and spells the word correctly. This is a new experience for me, but it’s important I realize Eli still needs to look at the pictures.

We make assumptions when we teach our vulnerable learners. If they can say a word, they also have an appropriate picture in their mind. Eli made me realize, again, that our students don’t always immediately connect a word to an image or concept. Instead, we, as teachers, need to supply it.

It takes time and practice, but it doesn’t take too long before Eli begins making those necessary connections.